Is it a good idea to tell your children that you have cancer, or is it better to keep it quiet? You would prefer to spare them. But is that actually possible?

Experience shows that ‘just’ telling what is going on causes the least problems now and in the future. If you don’t tell, you run the risk that your child will find out in some other way. Because children have antennae. They see and hear everything. A father who sits on the couch with red eyes, grandmother who suddenly shows up on the sidewalk, parents who spend a lot of time on their cell phones, children can sense that something is wrong. If they don’t know what is going on, they will look for explanations themselves. And their fantasy is often worse than reality.

In the picture: Thijs: ‘I knew it wasn’t good. Every time your cell phone rang you walked out the door.”

It is not wise to avoid the word cancer. The children are confused and may hear it at school or from their friends. Remember that the fear is usually within you. The greater the fear, the more difficult it becomes to talk about it.

By using the word cancer in the first conversation, the children can get used to it and they are not shocked if someone else suddenly starts talking about it.

In the picture: Sigrid:

“I was a twelve-year-old first grader when my brother and I were told that my mother had non-Hodgkin’s. I had absolutely no idea what it meant. neighbor crying in the kitchen, I slowly began to understand that it must be bad. It completely dawned on me when a boy came up to me and asked: “Your mother has cancer, right?”< /p>

Many parents are afraid that their children will talk about death. Most grandfathers and grandmothers have died of cancer, so many children understand that cancer can kill you. Difficult when your child asks such a question, but a good starting point for a conversation. After all, you can answer that there are different types of cancer and that you are starting treatment because you hope that everything will be fine again.

In the picture: “I felt desperate but wanted to survive. After a long time of hesitation, I told the children. Tim responded immediately. “Cancer, there Are you going to die anyway?” he asked. I told him that there are different types of cancer and that it can also be removed. Sanne is especially fascinated by my scar. She lifts her blouse every day to see if she might grow a zipper like that.”

Every child reacts to your illness in his or her own way. These reactions depend on the age, the character of your child and your own reactions.

No matter how young your child is, he or she feels your sadness and unrest. If you have to go to the hospital or feel very ill, you will have to temporarily outsource the care of your baby. You may also find it difficult to cuddle your baby. Because what if things aren't going well for you? Don't keep your distance, but let your child feel welcome.

You may think that toddlers and preschoolers are too small to be informed. They are still so young and still have so much to discover. But toddlers and preschoolers also feel when something is wrong. They become more restless and rebellious. Explain in simple terms what is going on and what the short-term consequences are. Something like: 'Mom is going to the hospital because she has a lump of cancer cells in her breast. The doctor has to take that out. She will be away for the night and you can sleep at grandma's.' A rag doll, bear or other cuddly toy can provide comfort.

Note: Preschoolers and toddlers often love to trumpet something around. If you don't want the entire neighborhood to know what is going on at home, agree on what your child can and cannot say.

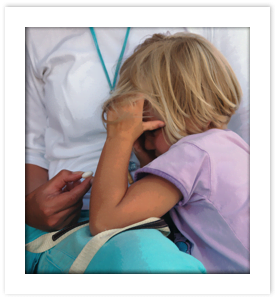

From the age of six, children are often very interested in facts. Read the information specifically for your child on this site together with your child. We also made animations. At this age, children often enjoy being allowed to go to the hospital. Because seeing is knowing. There are also those who give a speech about cancer. By preparing this together you will discover whether your child has understood it. Encourage your child to not only talk about cancer and the treatment, but also about what it does to him or her.

Stephanie:

"The presentation about Dad's brain tumor went really well. I told them what radiation treatment was and that I had been involved. There were a lot of questions. I also told them not to think I was sad, because I don't like that at all.

To move into a room or not. Going to work or study far from home or staying near the parental home. Young adults have to stand on their own two feet, but will also worry about the situation at home. Sometimes they put their own activities aside to take extra good care of you. Of course you also have your own wishes and expectations. What can your children do for you and to what extent can they be themselves and lead their own lives?

In the picture: A mother: “I would prefer to keep her close to me. After all, I don't know how long I have left. At the same time, I realize that it would be better for her if she could just do what she is good at.”

Children react just like adults. They are sad, scared or angry, walk around with feelings of guilt, feel unhappy and abandoned or act very tough and pretend that nothing is wrong.

Kinderen kunnen intens verdrietig zijn. Bij jonge kinderen is dat verdriet vaak van korte duur. Even is het heel heftig om daarna verder te gaan alsof er niets aan de hand is. Dat is heel gewoon. Soms komt het verdriet zomaar opeens naar boven. Tijdens het naar bed gaan bijvoorbeeld, onder de afwas of op school. Oudere kinderen kunnen langer met verdriet bezig zijn.

In het plaatje: Saskia:

"Mijn kinderen zijn vooral ’s avonds verdrietig. Kelly komt er tegenwoordig wel heel vaak uit en Joost wil het liefst elke avond bij ons in bed slapen."

Sometimes a child does not show sadness. Because just as you tend to protect your child, your child tends to protect you. Some children express themselves by writing, for example in their diary or in poems.

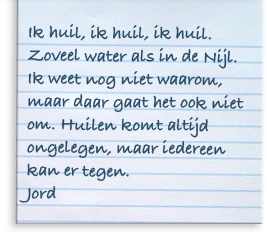

In the picture: Jord:

"I'm crying, I'm crying, I'm crying. As much water as in the Nile. I don't know why yet, but that's not the point. Crying is always inconvenient, but everyone can handle it."

Talk about sadness. Share how you deal with grief. Tell them what helps and what doesn't. Find distraction, cry together and laugh together. Is your child inconsolable? Get help and tell him to think about nice things too.

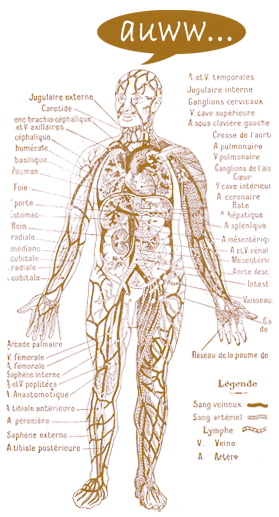

Many children are afraid. Afraid of the hospital environment, of changes, of the impending loss of the sick parent, of the loss of the healthy parent or of dying themselves.

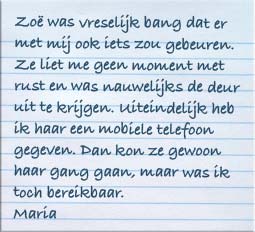

In the picture: Maria: "Zoë was terribly afraid that something would happen to me too. She wouldn't leave me alone for a moment and could hardly get me out the door. In the end I gave her a mobile phone. Then I could she just went about her business, but I was still available."

Some children are afraid that they will get cancer themselves. They think cancer is contagious, or know the concept of heredity. Tell them that cancer is not contagious and that heredity does not play a significant role in the vast majority of cases. If this is the case, doctors can investigate this. Talk to your doctor or nurse if your child has any questions about this and take them with you so they can ask questions themselves.

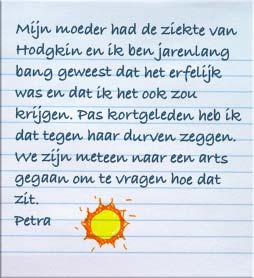

In the picture: Petra:

"My mother had Hodgkin's disease and for years I was afraid that it was hereditary and that I would get it too. Only recently did I dare to say that to her. We immediately went to a doctor to ask how that's it."

Children also look for causes. There are children who blame themselves for the fact that their father or mother is ill. They think they said, did or thought something that caused cancer. Sometimes there's more going on in those heads than you think.

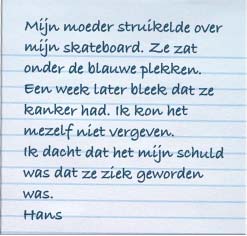

In the picture: Hans:

"My mother tripped over my skateboard. She was covered in bruises. A week later it turned out that she had cancer. I couldn't forgive myself. I thought it was my fault that she got sick."

Some children are angry. Angry because the whole world has changed, because home is no longer 'home', because it is their father or mother who is sick. Teach your children to deal with that anger.

In the picture: Dick:

"We hung a punching bag in her room to hit. Not a door was left intact and Tim also had a hard time. We said that we could all understand it, but that she should do something else with her anger. doing."

Children sometimes seem indifferent. They cannot or do not want to show their sadness and prefer to be 'normal'. Try to respect your children in how they deal with the situation and give them space to process it in their own way and in their own time.

In the picture: Daniel:

"At school they sometimes told me that I had to show myself more. But how? Should I sometimes start crying because my father is so ill? Well, no. That pain comes from within. Nobody else understands that. ."

Stomach and headaches are common. Sometimes the cause of these complaints is easy to determine. Then it is due to over-tiredness, going to bed too late, irregular or worse eating. Or maybe your child has the flu, an infection or a fight with a friend

Bottling up worries can also cause physical complaints. “It gives me a stomach ache” or “my head is so full” are recognizable expressions for many children. Your children usually know what helps and what doesn’t. Distraction, a cup of warm milk, rinsing your worries down the drain with the shower water, there are many options.

And then there is the fear of having cancer yourself. Sometimes your child has exactly the same complaints as you. A visit to the doctor can help.

Some examples of normal behavior:

- They crawl into their shell

- They require extra attention

- They are extremely helpful

- They take a step back in their development

- They are overactive

- They are sullen or aggressive

- They have a short fuse

- They are super sweet and overprotective

- They have problems with their homework or they do it very well

- They cannot fall asleep or have nightmares

- They no longer want to play with friends

These are all normal reactions to an abnormal situation, but that does not make them any less difficult. When to seek help? Persistent negative behavior is a cry for attention. But also way too sweet. Furthermore, persistent physical complaints are a concern, a child who no longer wants to go to school, children who already had problems before you became ill, a child who is extremely overprotective. Contact a good acquaintance, a teacher, a fellow sufferer, a nurse, the pastor, a child or youth psychologist. Follow your feelings, because you know your child best. Above all, try not to feel guilty if your child needs extra support. Parenting is hard enough, let alone when you’re sick.

During your period of illness, your children may have to help out more often with housework or care. There’s nothing wrong with that. Many children enjoy being able to do something for their parents. Even though these are tasks that they would otherwise not take on so quickly. But sometimes they step in too often or are given responsibilities they cannot handle. Get outside help.

Pay attention to your child’s behavior, not only at home but also at school and the sports club. Be especially aware of changes. Are there problems at school? Does your child suddenly no longer feel like going to athletics? Has the extreme walker suddenly become a home-sitter?

Inform the school in a timely manner about what is going on. Keep the teachers and mentor informed and agree to sound the alarm if something goes wrong. Indicate what you and your child expect from the teachers. Should they pay attention to it or not and to what extent? Is there someone your child can go to? Point out the teachers to this site.

Many children like it when the school has been informed, but they want everyone to keep doing things as usual. They simply don’t want to be an exception. They may also want to give a book review or speech about cancer.

If you care for your children alone, the news that you have cancer will probably hit you extra hard. But even if your ex-partner has cancer, you will wonder how best to guide your children in this. Find someone you trust with whom you can share your concerns.

If you care for your children alone, the news that you have cancer will probably hit you extra hard. But even if your ex-partner has cancer, you will wonder how best to guide your children in this. Find someone you trust with whom you can share your concerns.

Openness is also important now. It is important for your children to know that there are adults who are there for them. Don’t hesitate to call on family and friends and make plans together about who can step in or help. Know that there are options to receive additional financial support for childcare and informal care. Don’t forget to arrange guardianship and your estate properly. Make sure as much as possible is on paper. It gives you peace of mind when you have those arrangements behind you. You can then focus on your treatment and life again.

If possible, re-establish contact with your former partner and try to be on the same page as much as possible. Support each other. Do it for the kids.

If the prospects are poor, talking about death is inevitable. The children may want to know how this will work, whether anything can be done about it and what will happen to them.

As difficult and painful as it is, encourage them to come forward with their questions. Some children close themselves off or prefer to talk to others. That’s also good. They need time and safety to express their grief. Every child seeks his or her own path.

Looking back together on everything that has happened in recent years can give direction to your feelings and those of your children. Looking at photos, crying, making a book of beautiful and crazy incidents, sitting together without words, try to find a way that suits you best. It can help to get a book with death as a theme.

Maybe Achter de Regenboog is something for your children. This foundation supports children and young people in coping with the (upcoming) death of a parent. For more information, visit www.achterderegenboog.nl.

A number of support centers for people with cancer and their loved ones also offer programs for children and young people. Visit www.IPSO.nl for a center near you.

- Continue to inform your children and prepare them for any changes.

- Try to keep it concrete and clear. Use the information on this site, books and brochures. Did they understand what was said?

- Respond to questions and encourage them to ask questions to your doctor or nurse.

- Don’t promise things you can’t deliver.

- Keep your ears and eyes open.

- Have you ever shared anything about your own feelings? Tell them what helps.

- Some children (families) simply don’t talk much; that’s okay. You can also watch a movie together, listen to music or go to the forest.

- Listen to what your child says ‘between the lines’.

- Every child has their own ‘handbook’. You know your child best!

- Going to bed on time and going to school remains important.

- Maintaining structure and setting boundaries takes energy, but your children need it and you get a lot in return.

- Don’t hesitate to consult an expert.

- Take time for fun things. Life also goes on.

Information is needed to properly care for the student. Usually parents or a loved one share what is going on. If that is not the case, it is important to take the initiative yourself and ask the parent(s) questions such as: What exactly is going on? Is the parent admitted to the hospital? Is anything known about the severity of the disease? What are the prospects? What has already been told to the student? How do parents see the role of the school? What information may be shared with other parents and students? Who is the contact person?

Not all parents will want or be able to talk about cancer. There are major differences within existing religious or cultural groups in how they think about and deal with the disease. Don’t judge, keep talking to each other and learn from the parents. Ask them how you can best help their child and ask about any wishes regarding school.

After consultation with the parents, enter into an individual conversation with the student. Try to get an idea of what the student already knows and how the student deals with it. Usually the question “How are you?” be answered with “good”. Ask open questions. Let the student talk about the home situation and ask questions. Does the student want to inform classmates and other students and, if so, how? Which colleagues should be told?

Cancer is a serious disease that can be life-threatening, but will not necessarily kill you. Depending on the type and extent of the disease, all kinds of treatments are possible. Most treatments are aimed at healing. Or they ensure that the cancer stays away for as long as possible or even becomes chronic. So someone can live with cancer for a very long time. Unfortunately, there are also types of cancer that are so aggressive that people die from them. So there are many different forecasts and outcomes.

Remember that many adults and children tend to rely on examples from their immediate environment. Almost everyone knows someone with cancer. But every form of cancer and every treatment has its own specific course.

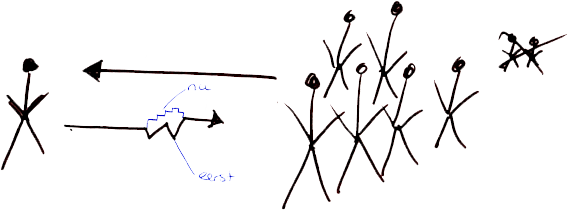

Sometimes it seems as if students are hardly sad. They go to school, attend classes and do their homework as if nothing has happened. Children cannot be constantly concerned with sadness. They need distraction. However, that does not mean that the sadness is not there.

Young children often react primarily at first and then move on to the order of the day. Older children want to function as normally as possible, but at the same time seek recognition for their situation. Look and listen carefully to what students say between the lines and radiate non-verbally. Give them space to express their feelings, but also provide structure and support.

"It was difficult for an outsider to see, but if you looked closely, you could definitely see that something was going on. She just functioned differently. She often lingered after lessons. Then she wanted to say something, but probably didn't know how or what. When I once took her aside and asked if she wanted to tell me something about home, the whole story came out. She talked for an hour."

Many students whose father or mother has cancer are afraid. Fear of the hospital environment, of the impending loss of the sick parent, of the loss of the healthy parent or of becoming ill themselves. As a teacher you can't do much with that fear, but it is in the minds of the students and it can keep them quite busy. Listening is also very important now.

There are children who blame themselves for the fact that their father or mother has cancer. They think they said, did or thought something that caused the cancer.

A teacher: “I was shocked when he told me he thought his father's brain tumor was his fault. He had been playing bouncy ball and the ball hit his father's head. I recommended he see a doctor to talk to his father. He was very happy about that."

They may also feel that they are not trying hard enough.

Sheryl: "My mother was getting sicker and I couldn't do anything about it. The only thing I could think of was to try very hard at school. After her death, I wondered for a long time whether I should have worked even harder."

A lesson about cancer can be illuminating. This way, students can investigate for themselves what is true and what is not. Also discuss concepts such as disinformation and fake news, because all kinds of misinformation is also spread on the internet.

“One of my students came up with the story that sunscreen is carcinogenic. Another talked about pathogenic substances in the vaccine against the HPV virus. The comments prompted me to teach a lesson about news and fake news.”

Most schools include children with a migration background. What do they know about the development of and management of cancer? Is it ever discussed at home? What ideas are there on this subject? Listen to your students, respect them, but also share the right information and knowledge.

Some students are angry. Angry at the cancer, angry at the many changes, because home is no longer home, because it is their father or mother who is so ill. They are angry at everything they encounter. A short fuse is therefore very common. It is important to provide clear boundaries, rules and structure, but also to show attention and understanding. This helps students learn to deal with that anger.

Bonnie: “I'm angry at the fact that my mother is ill, that it had to happen to her, at the cancer itself..., sometimes I don't know what I'm angry about. Then I'll just be the teacher. There has to be someone to get mad at!”

Actually, it's about pseudo-indifference, because a lot is going on in their heads.

Daniël: "At school they sometimes told me that I had to show myself more. But how? Should I sometimes start crying because my father is so ill? Yes, no. That pain comes from within. Someone else understands that. none of it anyway."

Some examples of behavior that you can also observe at school:

- the student withdraws

- exhibits helpless behavior

- takes a step back in his/her development

- requires constant extra attention

- does extra well at school

- is overactive, sullen or aggressive

- has a short fuse

- has social problems

- has memory and concentration problems

- is overtired

Persistent negative behavior is a signal that the student needs help. It is often necessary to limit students. Bart wanted to talk about cancer over and over again, he could hardly stop. The teacher allowed him to talk for 3 minutes every day and if he got very busy he was allowed to take a breather in the hallway.

Also pay attention to the students who become very quiet and calm. Showing understanding and paying attention, an arm around them, a supportive conversation, all this can help many children. If something really threatens to go wrong, professional help is necessary. Consult with the parents about how to approach this.

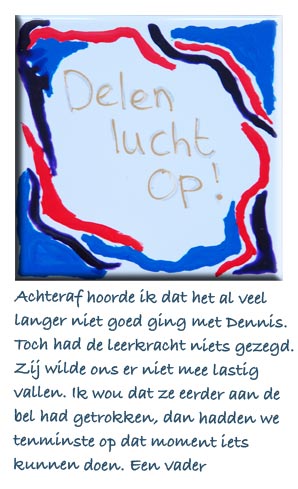

A father: “Afterwards I heard that Dennis had not been doing well for a long time. Yet the teacher had said nothing. She didn't want to bother us with it. I wish she had sounded the alarm sooner, at least then we could have done something at that moment.”

Of course, not all behavior can be attributed to the home situation. Sometimes there are just other reasons why things aren't going well at school. Heartbreak, fear of failure, arguments with a boyfriend... it's all possible.

“My head is so full!” is a frequently heard statement. That is of course difficult if you also have to learn. Look together with the student at what can be done about it. It is important that the student does not fall behind. Find a balance between the demands of the training and what is going on at home. Visitors will come by, parents have to go to the hospital, the medications have side effects and there is always the tension whether everything will continue to go well. Students whose father or mother has cancer are not only concerned, but often have additional responsibilities at home. All this has consequences for going to school and their ability to concentrate. So thinking along is necessary.

Subtle individual attention Most students want to be ‘ordinary’. They don’t want to be an exception, but they do want recognition. You will have to keep your finger on the pulse. You can do this by giving (subtle) individual attention. Start from the student’s needs and explore the possibilities together. This could be a personal conversation at a fixed time. But also a place where the student can withdraw or a time-out signal with which the student can indicate that he or she wants to take a break. Encourage the student to talk to whoever he or she feels comfortable with.

Often the student will not be able to indicate what he or she needs, in which case the initiative lies with you. You can make a big difference by actively thinking along.

Richard: “Mrs. van Rhijn read a story about a mother who had cancer. I didn’t dare say anything and I spent the whole time messing around with my pen. Still, I liked that she told something about it. On one Somehow I didn’t feel so alone anymore.”

Young people among themselves

Young people mainly communicate with their friends and through their own channels. Joys and sorrows are shared on TikTok and Snapchat. It is good to see how they encourage and support each other, even if one of the parents has cancer.

Stay informed

Think about how you can stay informed. Cancer is a disease that can last a long time and change at unexpected times. Students transfer, change teachers, classes or schools. This can cause data to disappear or be forgotten. Pass the information on to your colleagues and inform substitutes about the situation and agreements you have made with the child. Make sure you stay up to date and keep in touch with the parents. Provide a permanent point of contact.

Your own experiences influence how you view cancer and the way you pay attention to it. Try to clarify this for yourself and remember that no two situations are the same. Be open to your own and your student’s feelings. Are you emotionally able to guide your student well? If not, ask a colleague for advice.

Jacqueline: “Lesley’s teacher didn’t want to talk about it. She couldn’t handle it at all and pretended that nothing was wrong. Her replacement did ask how it went. Lesley came home completely happy, she should have told her. about the hospital visits and the injections her father received.”

Safety

The most important thing is that you provide safety. A place where students can be themselves. Where they are part of the group, but their individuality is also recognized. For example, one student will benefit from fixed agreements and the other will be able to indicate automatically when he or she needs something.

Respect

Students who want to talk about their sick father or mother in class deserve all the respect. Hein no longer wanted to go to school when he was called a ‘wimp’ and ‘gay’ after he told them that he helped his seriously ill father with washing and dressing. If there is sufficient safety and respect, very special things can happen. After much hesitation, Nick asked the class the following question: “Do you also find it so bad to see your father or mother cry? And what do you do then?”

Swearing

Unfortunately, cancer is often used as a swear word. Students who have a father or mother with cancer are extremely sensitive to it. It is not uncommon for them to come to blows in response to swearing about cancer. Do not tolerate swearing and make it a topic of discussion.

Lessons about cancer

Also broach the subject of cancer if there is no immediate reason to do so. You will notice that there are quite a few students who are affected by it in one way or another. A subject such as heredity can also give rise to further reflection. If necessary, refer children to the GP. If you broach the subject of prevention, be aware that some students are already dealing with cancer at home. (also see guilt feelings)

Ruby: “I know that smoking can give you cancer. But some children say, “It’s their own fault, you fat bastard”. Well, I think that’s stupid, they just don’t know what they’re talking about.”

Speech or paper

Making a speech or profile paper can be an excellent outlet to tell something about cancer. Although most students do not like to be in the spotlight, such a school assignment can give them the push they need to discuss the home situation.

Lotte: “For my economics profile paper, I set up a bracelet campaign against cancer. It was a big success. I feel like I was really able to do something.”

When a parent of one of your students dies, that student desperately needs your support. If you were already aware of the disease process and the prospects and were permanently involved, you probably saw it coming and were able to prepare.

What will you tell the class? What is your own role and what is that of your classmates? How can you support the student? There are several ways to help. You can go to the condolence and/or funeral, organize something with the class, write a letter or card.

Kiki: “When my mother died, there were a lot of classmates at the funeral. The mentor also came along. I thought that was quite nice.”</em >

Yannick:”After my father passed away, I received a card from my gym teacher. I loved that he thought of me. If I had been a girl, I would have given him a kiss.”

For more information about palliative care, death and grief, visit the pages for children, our book list, and or at www.in-de-wolken.nl.

- I was so happy that my teacher finally asked how my father was.

- I don’t talk about it at school, not everyone needs to know.

- I had passed it on to the mentor, but during the report discussion it turned out that no one knew anything about it.

- Cancer, cancer Jew, cancer whore, I’m increasingly tempted to hit.

- I would actually like to give a speech or write a paper about it.

- I was shocked when the biology teacher suddenly started talking about cancer.

- My math teacher reacted very strangely when I told her. It seemed like she didn’t want to hear it. She immediately started talking about something else

- What’s the point of doing homework? My mother is going to die anyway!

- Sometimes I feel like I’m the only one. Don’t you know someone who has experienced the same thing?

The diversity of these statements shows how complicated it is. Individual coordination is necessary, but a guideline can provide guidance. Also read the pages for the children.

- Offer maximum security and create a safe atmosphere

- Show attention and understanding

- Provide clear boundaries and structure

- Find a way to give space to emotions

- Keep in touch with the parents

- Ask yourself what this situation does to the other students

- Ensure the right balance between homework and other school tasks and take the home situation into account

- Discuss with the student what to do if things aren’t going well at school

- Be aware of your own knowledge and skills

- Remember that cancer is a disease that can last a long time and change at unexpected times

- Guard your own boundaries and seek help if necessary

- Take a look at the book At night I hear the comfort birds singing (see orders)

Many parents wonder what is going on in their children’s heads. They worry and sometimes feel guilty. What do the children take with them from being sick? Do they express themselves sufficiently? Can they still be carefree? Are they damaged by what they experience?

It starts with the question of whether they should tell them that they have cancer. Parents want to protect their children. But children have antennae, they hear and see that something is wrong and develop their own fearful fantasies about it. You help parents by pointing out to them that not knowing is worse than knowing.

It is understandable but not wise to avoid the word ‘cancer’. If parents talk around it, it confuses children and they will probably hear it from someone else instead of their own father or mother. Ask parents what they have told their children, give them information and help them find the right words adapted to the age and development level of the children.

Many children are sad. Parents often find this very difficult. It is painful to realize that your child is sad about something that is happening to you. It helps if parents can think about what to do with that feeling. After all, every child will sooner or later have to deal with sadness. Sometimes talking helps, other times it helps to walk or cycle together.

Sometimes the reaction is the opposite: it seems as if children are hardly sad. This is also often difficult for parents to understand. Tell them why children do that. Because they do not want to burden their parents with their grief or because they do not want or dare to admit those feelings. The fact that children are indeed worried can often be clearly seen and heard in an indirect way. In their drawings and poems or in the music they listen to.

Feelings of anxiety also occur. Many children are afraid of the hospital environment, of changes in appearance, of the impending loss of the sick parent, of the loss of the healthy parent or of dying themselves. If children have ideas about cancer, treatments or dying that are incorrect, explanation is necessary. This way the ghosts in their heads can become less. Explain to parents and children that fear has a tendency to suddenly overtake you and think together about what you can do about it.

Sometimes a visualization exercise helps. Put the fear in a jar, screw on a sturdy lid and put the fear, jar and all, in the cupboard. Or: get in the shower, rinse away the fear and let it flow down the shower drain.

There are children who try to allay their fears by exhibiting compulsive or avoidant behavior. Luca straightened the table every day, only then could she be sure that her mother would not become even sicker. She also always washed her hands and was only allowed to walk on the right-hand paving stones. It was impossible to get Jonas to the hospital with a stick, even when he himself needed a doctor. Naturally, professional support is necessary in these types of situations

Some children blame themselves for the fact that their mother or father has cancer. They think they said, did, or thought something that caused cancer. Be aware of the fact that most children cannot give voice to those thoughts.

You can ask older children if they know where cancer comes from. To young children, you can say: some children think that… what do you think? Also here it is clear that giving an explanation, in this case where cancer comes from, is very important.

Many children are angry. Angry because the whole world has changed, because home is not home anymore or because it has happened to their mother or father of all people.

Physical activity can channel these feelings. Make parents and children aware of possibilities such as dancing, fitness, street dance, kicking a ball or hitting a boxing ball. Making music can also be a good emotional outlet.

Swearing about cancer often really gets to you. It gets even worse if the swear word “kanker” (cancer) is used on purpose. As a professional helper you can try to make the children more resilient. Talk about what to do if there is swearing going on. As a child, do you opt to attack? Do you build a wall around you so that the arrows do not hit you like that? A class presentation can help. Older children could start a poster action or make a film clip on this subject.

Sometimes children become extra caring. That is nice, because it is difficult enough as it is for parents. It goes without saying that children have to stay children too. It should not go so far that a child does not go to school anymore because she/he has to look after a parent, or because the mother or father is in hospital, or that she/he has to look after her/his younger brothers and sisters.

As professional helper you can be the children’s advocate and sometimes your role is as a mediator.

Children who have a mother or father with cancer can feel very lonely. It is as if they are the only one with an ill mother or father. By bringing together children who are in the same situation, you allow them to discover they are not an exception. Furthermore, they can learn from each other and give each other tips and advice. Refer them to a children’s or young people´s group in your neighbourhood, and point out the chatroom on this website or other websites.

Can you deprive children of hope?

No.

However bad the situation, every child and every parent needs hope. Sometimes dreams come true, sometimes they do not. Prepare the child for a situation that can also be different, but do not deprive them of hope.

Interventions range from giving explanations and talking to drawing together, writing, boxing, filming, making comfort boxes or treasure chests, visualizing a safe place, making music, playing a game or taking a walk. The choice of intervention depends on the age level, attention span and interests of the child or young person. For young children, games, reading books and stuffed animals work best. Older children benefit more from music, games, photos or working with written texts.

But regardless of their age: ultimately what matters is what you discuss together. Above all, try to be flexible and creative in your approach. Sometimes one method works, sometimes the other. This applies both when you work with one child and with multiple children at the same time.

Maybe you haven’t worked much with children as a counselor or haven’t thought about the possibility. Maybe you find it difficult or it hits too close to home. Remember that it is also nice for children if they can turn to someone. Communicating with children is not difficult at all. Just do it!

A GP: “I can talk to that thirteen-year-old girl, but what do I do with the eight-year-old girl?”

Some questions that many children have. You can find the answers on the site.

- How come my father/mother got cancer?

- Are you sure that my father/mother will not get better?

- How does chemotherapy work?

- What is radiation?

- Can children get it too?

- Is cancer contagious?

- Is it weird that I don’t feel anything?

Adolescents and young adults are not only concerned with themselves and their own future, but also with life in general. Having a father or mother with cancer turns life upside down. They can struggle a lot with this and need someone who really listens to them.

Don’t assume that teenagers understand everything. They sometimes pretend, but the danger of overestimation is great. Therefore, also use clear and concise language for teenagers and give them time to think about things. Keep in mind that they may react differently than you expect!

Claudia: “That nurse asked a hundred times if I really understood what was going on. Of course I know she is dying and I think it’s terrible. But I don’t have to tell her that, do I?” em>

A community nurse: “Whenever I came to that patient’s home, his son was sitting behind the computer. I’m sure he was listening. Looking back, I sometimes think I could have asked him if he wanted to know something…”

By including the subject of ‘children’ as standard in conversations, you make parents aware of the importance of involving their children. Encourage parents to take their children to the hospital. Regularly ask how the children are doing and be open to questions from and about children. Are they allowed to come to your office hours? Are you willing to answer their questions? Do you have information material for them? Do you know who to refer them to if necessary?

A radiotherapist: “I always advise parents to take their children with them to radiation treatment. This way it becomes immediately clear what we do. Of course you have to make some time for them.”

A nurse: “At our hospital we have special afternoons for children. We explain what cancer is and how it is treated. We show everything. The kids love it.”

Sometimes children take the initiative to write a letter or ask for a meeting with the treating doctor. Encourage them to write down and ask their questions.

When told that their father or mother has cancer, many children will wonder whether their father or mother is dying. Hopefully the treatment will offer perspective and this can be passed on to the children. But if the prognosis is poor or the disease returns and there is no hope, the children have a right to know this too. Because just like adults, they need time to prepare for saying goodbye and that is only possible if they know what is going on.

Don’t leave the children out in the cold. Looking back with their sick father or mother on everything that has happened in recent years can give direction to their feelings. As a care provider you can support the children and offer them a place where they can express their grief. Parents sometimes need tips and advice about what they can leave behind or how they can involve their children in separation.

This is how children can:

- Consider a place at the cemetery

- Thinking about a text on the card

- Help dress their deceased parent

- Painting the coffin

- Selecting music for the funeral

- Help carry the coffin

- Give music, a letter or hugs

Parents

It may be that parents do not want openness at all. Denial, education and faith play an important role in this. You can explain to parents what it means for their children if they remain in the dark. If this does not lead to the desired result and parents really do not want openness, then that is what it is. Respect their boundaries and stand by them, because only then will you move forward.

Children

Some children really don’t want to talk. Apparently the fear is too great. Respect their boundaries. By being open and honest, radiating calm and confidence and not forcing anything, you offer the children a safe starting point. Sometimes you get unexpected reactions.

A psychologist: “If he says five words it’s a lot, usually he draws or we walk for a while. Somehow that’s enough. Recently he said it really helped him. After all, we talk so well!”

Emergency workers

Every profession has boundaries. See what you can handle and want. Take the time for reflection. Talk to colleagues about situations you encounter and exchange experiences.

- Inquire about the children, ask what they have been told and how they are doing

- Tell them that not knowing is often worse than knowing

- Explain that it is okay to use the word ‘cancer’

- Alert parents to possible feelings of guilt in their children

- Remember the children’s names

- Do not let the questions be based on chance, but ensure they are structurally embedded

- Encourage parents to bring their children with them

- Make sure your knowledge is kept up to date

- Make sure you have sufficient information material

- Also ask the children themselves

- Point them to this website

- Indicate that they can come to you